[This is an Op-Ed that was originally published in text-only form yesterday in the weekly free newspaper Our Town, serving Manhattan’s Upper East Side]

Mayor Bloomberg has been pushing to rebuild and reopen a shuttered marine garbage transfer station (MTS) in the Manhattan neighborhood of Yorkville since 2002. Many nearby residents vociferously oppose the plan because the old MTS locally worsened air quality, noise pollution, and led to foul garbage smells, and they anticipate similar or worse problems with the new, larger MTS.

As an oceanographer and resident of Yorkville, I am writing with a dissenting viewpoint that’s sure to start some trash talking.

In 1999 the MTS was shuttered because of decreasing use, after the Staten Island Fresh Kills landfill was closed. Since then, trash has typically been driven through less affluent communities and transferred to long-haul trucks for shipment to other states as far off as South Carolina. If the MTS is rebuilt and reopened, garbage trucks from most of the eastern half of Manhattan will converge at the MTS on 91st Street at East River, where garbage will be transferred inside a closed building to sealed shipping containers and placed on barges for long-distance transport. This would reduce city-wide truck traffic and air pollution, and (in the long-run) save a lot of money. It would also address the injustice of trucking most of Manhattan’s trash to low-income communities (Newark and Jersey City).

Map showing the site of the existing marine garbage transfer station (MTS), where a new expanded facility is scheduled to begin construction in 2012. The project is under appeal.

The MTS’s opponents have been distributing printouts of a new letter around the community that can be signed and sent to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). This latest effort to stop the MTS collides with my area of expertise, oceanography — they are claiming that the “delicate ecosystem” of the East River will be badly harmed, and that this threatens striped bass fish.

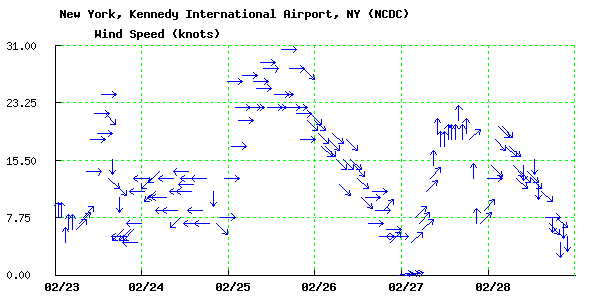

The East River is not a “delicate ecosystem”, as the letter claims – it is a heavily urbanized waterway, with large boat wake waves and strong, dispersive tidal currents. Striped bass aren’t likely to be vulnerable to the proposed increase in activity, nor the development’s relatively small footprint. They lay their eggs elsewhere, in freshwater, and the striped bass found here are large and strong enough to evade boat traffic.

Moreover, there is a much more compelling set of factors that should override the delicate ecosystem argument. Opening the new MTS will prevent substantial carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions that currently result from trucking garbage over long distances within and beyond NYC. CO2 emissions are enhancing the greenhouse effect, causing global warming of the atmosphere and ocean. This ocean warming is pushing fish like striped bass poleward to find cooler waters, and threatens to eliminate the world’s immobile ecosystems, such as coral reefs.

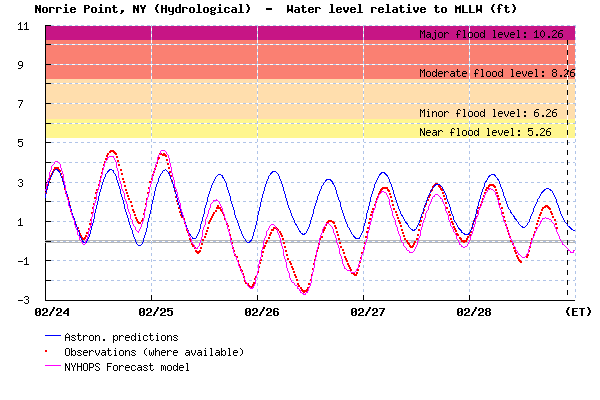

The heating of the ocean and melting of glaciers cause sea level rise, which should be a very serious concern for this low-lying neighborhood. Sea level around NYC is expected to rise between 1 and 4.5 feet by 2085, raising flood levels for coastal storms like Hurricane Irene higher and giving them much greater destructive potential.

Seawater briefly surged over city seawalls during tropical storm Irene, an approximately 1-in-10 year coastal flooding event. Water levels for a 100-year event are thought to be about 2.5 feet higher, and sea level rise will add 1 to 4.5 feet to that height by 2085.

Furthermore, CO2 is causing ocean acidification, with poorly understood but potentially profound implications – the world’s oceans are already 30 percent more acidic than in pre-industrial times, and is projected to become a factor of 2 to 2.5 times more acidic in the next 100 years if we don’t dramatically reduce our emissions.

For those who care about delicate ecosystems: CO2 makes seawater more corrosive for many of the microscopic organisms that form the base of the food chain.

None of this is new to several prominent environmental groups that have spoken up to support the marine transfer station, including the NY League of Conservation Voters, the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Organization of Waterfront Neighborhoods and Environmental Defense Fund. And it also has the support of New York City environmental justice advocates.

New Yorkers can take pride that Mayor Bloomberg is the chair of a coalition of 58 major global cities taking action as the Cities Climate Leadership Group. Global warming is a major concern for Bloomberg, in part because we are a city of islands and sea level rise may eventually force the city to rebuild low-lying infrastructure like FDR drive where it passes by Yorkville. As always, the steps we are taking in NYC are having a much broader, global influence.

The MTS is an important part of PlaNYC 2030, which prepares the city for expected population growth, improves NYC air quality, and helps reduce global warming, sea level rise and ocean acidification. Detailed information on the MTS and the broader Solid Waste Management Plan is available on the NYC Department of Sanitation website. I recommend people get involved and read the plans for themselves, as I’ve personally found them to be highly detailed and address most of the concerns residents have raised about the project.

While we must be vigilant and hold the Department of Sanitation to their commitments to maintain a healthy and clean local environment, residents should support the MTS plan because there are concrete, long-term benefits for Yorkville, NYC, and people and ecosystems around the globe.